Dragon lizards in the semi-arid regions of western Queensland are doing it tough. Our study species, the central bearded dragon is no exception. They are very thin on the ground, more so than might be expected from historical accounts of their abundance, a great frustration for researchers Kris Wild and Phil Pearson from the Institute for Applied Ecology who are studying them. Not only do they face the risk of catastrophic rates of sex reversal as our climate warms, and high predation rates from native predators such as raptors, but now they have the feral cat to contend with.

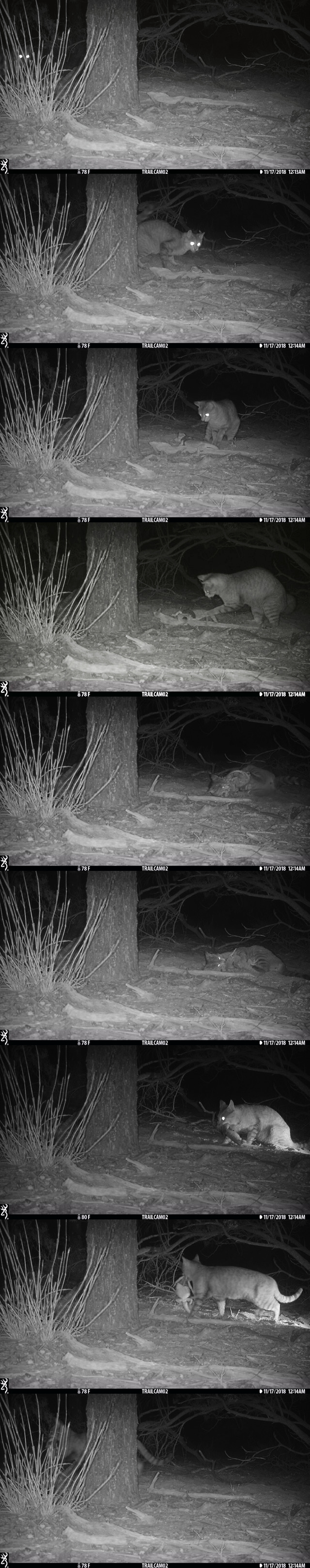

This threat was brought home by our recent experience with Niña, a gravid female lizard we were following with $1,000 worth of kit on her back. She was taken by a feral cat. We got full footage of this because we were following her with trail cameras to see where she deposited her eggs.

It is a mystery as to why Niña was out during the night, leading to the unfortunate encounter around midnight.

To our distress, puss pounced then played with Niña, killed her, walked off with her, ate one leg, and discarded the remainder destined to be picked over by birds in the morning. Clearly the cat was not particularly hungry, but nevertheless, did what cats do.

Almost half of the animals we have been tracking in Bowra Conservation Reserve have been taken by one predator or another over about two months, and given the age of the lizards and time to maturity, such a predation rate seems exceptionally high. We hope our data will provide valuable information on how much feral cats are contributing to the low abundances of these lizards.

Feral cats are an unwelcome addition to the Australian fauna because, as highly effective predators, they have the potential to alter the population dynamics of prey species, in some cases, potentially leading to local extinctions. Our species of native wildlife, having been isolated on our island continent for many millions of years, may be particularly vulnerable to the introduction of an exotic predator, such as the domestic cat gone feral.

Cats eat an astonishing array of native species, in addition to introduced prey such as the rabbit, mice, and black rats. Where these exotic prey species abound, impact of feral cats on susceptible native fauna may be increased through a `subsidy' effect. The most vulnerable species are those that occupy open areas, are small (< 220 g) and those with behavioural traits that assist with visibility and capture.

While cats eat native animals, and estimates of the quantities of animals eaten by feral cats each year are cause for concern, the impact of cats is difficult to quantify. We have known since Malthus that life reproduces itself in great surplus, and that predation is a natural feature of most if not all species life histories. As one wag put it, "we eat cows, but they are not going extinct".

Nevertheless, individual cases of the examination of the stomach contents are quite alarming. A feral cat shot at Rocky Downs in 1993 had in its stomach, 24 painted dragons, 3 juvenile bearded dragons, two species of earless dragon, 3 skinks, one Zebra Finch and one house mouse. The photo was taken by John Read (ecologist Olympic Dam SA).

Feral cats clearly eat a wide range of reptile species but, part from the pub test, evidence of impact has been hard to quantify. However, recent studies have provided detail on the impact of feral cats on the abundance of their prey. Feral cats cause high rates of mortality for many bird and mammal species, and are responsible for the extinction of at least 18 species of island-endemic vertebrates. Their impact is not dramatically lessened as abundances decline, and so already threatened species can be brought to the brink of extinction by the added predation pressure.

Danielle Stokeld and her colleagues recently undertook the necessary experimental studies in Kakadu National Park. They found an increase in the abundance of reptiles in cat-excluded plots that was twice the rate when compared with cat-accessible plots.

So, our unfortunate experience with Niña may have deeper relevance for her species in the semi-arid regions of western Queensland. Cats are one of a tyranny of 1000 cuts, maybe the one that tips this species and others over the edge when things get tough.

For further information and access to photographs, contact Kris Wild on kris.wild@canberra.edu.au. Many thanks to volunteer Hunter Warwick, who had the foresight to bring his trail cameras along.