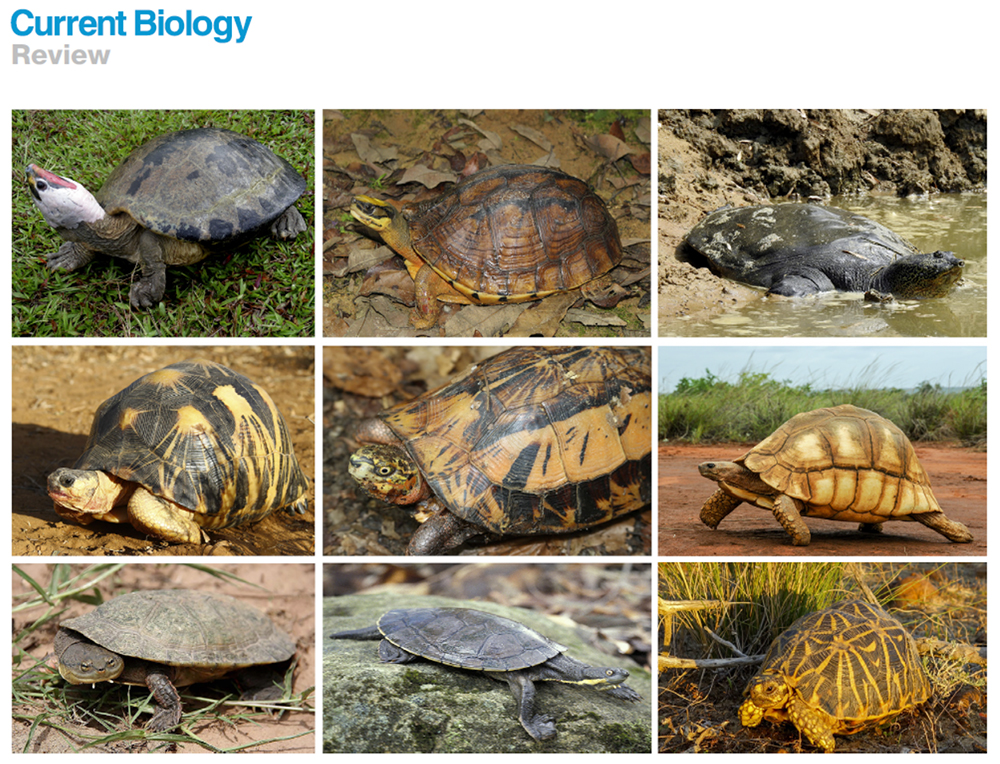

Fifty-one international experts today published the most comprehensive study of the extinction risks for turtles and tortoises in Current Biology. Turtles are in trouble. More than half of all 360 turtle and tortoise species face imminent extinction if current trends continue. Australian turtles feature prominently in the list of species of greatest concern.

Hundreds of thousands of turtles and tortoises are collected for the wildlife trade every year. Turtles and tortoises are long-lived and slow-growing species, which means they can’t reproduce fast enough to replenish their populations that are taken from the wild. Some of the biggest confiscations have occurred in the past few years. Last May, Mexican authorities made the largest-ever confiscation of live turtles. Fifteen thousand turtles were being smuggled from Mexico to China. In 2018, two confiscations of radiated tortoises in Madagascar, just months apart, totaled nearly 18,000 animals.

Three species of turtles and tortoises have gone extinct in the last two centuries, but that number will climb if the trade isn’t curbed.

“A long slow life trajectory worked for them for millions of years, but it doesn't serve them well in the modern world in the face of humans poaching them and destroying their habitat,” said Craig Stanford, lead author of the paper. “Thirty years ago, the radiated tortoise was one of the most abundant tortoises on the planet. However, following a coup in 2009, poaching increased dramatically, and their population has been in freefall since then because of the combined effects of smuggling for the international pet trade and consumption of their meat by local people.”

“A long slow life trajectory worked for them for millions of years, but it doesn't serve them well in the modern world in the face of humans poaching them and destroying their habitat,” said Craig Stanford, lead author of the paper. “Thirty years ago, the radiated tortoise was one of the most abundant tortoises on the planet. However, following a coup in 2009, poaching increased dramatically, and their population has been in freefall since then because of the combined effects of smuggling for the international pet trade and consumption of their meat by local people.”

If humans reduce the demand for turtles and their eggs for food, it would take pressure off of many threatened species. The authors of the paper urge governments to enforce existing laws and effectively implement the CITES convention, which regulates the international trade of endangered and threatened species to prevent overexploitation.

“International trade in turtles, and their parts and products, has been recognized for decades as a severe threat to some turtle species and populations” said Peter Paul van Dijk, director of the turtle conservation program at Global Wildlife Conservation. “What has not been widely recognized is how the global demand for turtles rotates between countries and continents, vacuuming up one population and species after another, with disastrous results for their survival.”

In addition to ending the wildlife trade, there are other actions that would protect turtles and tortoises. Many of their habitats in the wild are under threat, often being destroyed as a result of human activities. However, there are still habitats that are healthy enough to support large numbers of turtles and tortoises. Scientists have identified 16 hotspots around the world that are home to a wide diversity of species and where protection of remaining natural areas will make a great difference.

The paper’s authors argue that local communities must be included as partners in protecting turtles and tortoises and their habitats. Ecotourism may be a model that can benefit humans and species living near them.

“There are number of other ways to encourage turtle conservation including stimulating turtle-based ecotourism—also known as turtle-watching and turtle life-listing—following a bird-watching model,” said Russ Mittermeier, chief conservation officer for Global Wildlife Conservation. “What is more, we need to highlight more clearly the roles that turtles play in providing critical ecosystem services such as energy flow, nutrient recycling, scavenging, soil dynamics, and seed dispersal in the terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems in which they occur, all of which tend to be overlooked.”

Technology can also help conservation biologists monitor habitats and populations. Side-scan sonar and e-DNA allows scientists to identify where turtles are living without disturbing them. Other tracking technology like GPS and radio telemetry can also help scientists learn more about turtle and tortoise movements and habitat use.

Captive breeding and head starting programs could help certain species of turtles and tortoises, but in order to be effective there must be natural habitat remaining to release the animals. The Española giant Galapagos tortoise and the Australian western swamp turtle were both rescued from near extinction by captive breeding efforts. But it is difficult to breed some species in captivity, so it may not be possible to build healthy assurance populations for every species.

For further information and an Australian perspective, contact

Dr Carla Eisemberg, Charles Darwin University, carla.eisemberg@cdu.edu.au, Phone 0401 737884

Dr Ricky Spencer, Western Sydney University, r.spencer@westernsydney.edu.au, Phone 0400 020546

Dr James van Dyke, Latrobe University, J.VanDyke@latrobe.edu.au, Phone 02 6024 9712.

Dr Arthur Georges, University of Canberra, georges@aerg.canberra.edu.au, Phone 0418 866741